Author: Ian Thomas

Originally posted on Medium.com on June 26, 2019. Reproduced with permission of the author. For more of Ian’s writing on LARP and games design, go to https://medium.com/@wildwinter

Back in late 2017, Harry Harrold asked Rachel and me to help him put together the Musketeers game he’d been bullied into running. He also enlisted Bill and Kiera – who’ve always done our stunts, props, and ridiculous over-the-top moments – and we roped Dan and Damian in to help out as well. So, suddenly All for One was a Crooked House event, in association with Harry. And, as it was only just over a year away, we needed to start the design process. We like to get a head start on these things.

The design unfolded over the next year, mostly in conversations between Harry, Rachel, and myself, with occasional calls with the others. It changed direction a lot, and frankly it’s hard to remember all the variants, but here are some of the major decisions and the thinking behind them.

A List of Moments

We started with our standard approach to this sort of event: brainstorming a long list of ‘moments’ that we want the players to experience. I’ve written elsewhere about this design method; effectively we started by saying “what moments would make the players feel like they were in a Three Musketeers movie?” and writing down a long list. Things like: being in the fight in the laundry, swinging from a chandelier, brawling in the tavern, having breakfast between the lines at the siege of La Rochelle. By the time we’d finished, we’d listed several hundred of these moments, drawing from the 1970s movies and similar material in the same genre. We had a first pass to figure out what might be practical. Then we took a step back and considered the overall shape of the event.

Broad Strokes

Harry had started with an initial idea, which was to structure the event as if it were Hogwarts for Musketeers; you would start as a cadet, have lessons in swordplay and politics and etiquette, and then finally at the end you would stand before the King and take your oath as a full Musketeer at a graduation ceremony. Roughly following D’artagnan’s path – earning your place amongst the Musketeers.

This was a great starting point; it told us what the main physical setting would be (we hadn’t picked a site at this point), told us that we’d be breaking the event up into blocks of time (‘lessons’), and even better told us that we’d be breaking the cadets up into small squads – a bit like Hogwarts houses – which was interesting for a bunch of reasons.

Teaming Up

Splitting the cadets into squads would potentially give us rivalry and a sense of identity, as with the Hogwarts houses – but more importantly it gave us a small, bonded group. Which, given the movies are all about a small, bonded group, is perfect. Your best friends by your side, willing to clash swords and shout “All for One!” in unison.

This became the key decision for the game, and drastically affected how we’d design and plot out the game’s events. It was no longer a game focusing on an amorphous group of between 30 and 50 players; it was a game focusing on several small, tight-knit groups.

We decided each group of cadets should have a servant, to fill the place of Planchet from the movies. And that a group of cadets should be called a cadre. We settled on five cadres consisting of six cadets and one servant each, making thirty-five players in total; primarily because that fit with the numbers we were allowed to have at the venue we’d now settled on – a 17th Century house near Monmouth.

To Adventure!

So, an academy full of cadres of cadets, learning lessons and having rivalries. But surely that was Hogwarts, not Three Musketeers? How could we add in those elements from the movies that were on our wishlist of moments – chasing enemies across France, gambling and drinking in taverns, visiting the Queen at Versailles?

The cadets must be allowed to go and have adventures! In their separate cadres, as we wanted the cadets in those groups to have shared adventures that would strengthen their bond. We came up with two ways for this to happen:

The High Road

The first, and most obvious, answer was to adopt what we in the UK think of as ‘old-school linears’.

These were typical of University LRP club systems where so many of us started; a path through a wooded area, where a group of players would set out and have ‘encounters’ every so often along that linear path. At the start of the adventure they would typically be given a mission. Then they’d come across various groups of enemies or NPCs to talk to, some directly related to the mission, some just filler. Then eventually they’d reach the goal of the mission and achieve it (or die trying!).

Happily, our intended site had just such a wooded area within easy walking distance.

This would fit the shape of the event very well and would give us many more of our wishlist of moments – being able to send a cadre out to travel the Paris high road to intercept a message, or to pursue an enemy while fighting off the Cardinal’s Guards. It would also bring in plenty of nostalgia for the older British players, which was a nice bonus. Tom and Woody were ‘volunteered’ by Harry to run this for us.

However, it wouldn’t adequately answer our other aim – letting the cadres visit the Queen at Versailles, or wander the streets of Paris.

The Sound Stage

Since not long after we ran Captain Dick Britton and the Voice of the Seraph back in 2006, I’d wanted to set up something I called a sound stage. I’d thought about it for Dick Britton 2, but we put that event on hold. The idea was that we’d take a large empty space, set up a projector as a backdrop, and then add lighting, sound, other effects, and some very simple props, allowing the players to improvise wildly with a minimalist set – something they’d done spontaneously at the first Dick Britton and something we loved.

This was an ideal fit for the Musketeers event. With a sound stage, we could transport them to the rooftops of Paris; to the middle of the English Channel in a boat; to a far-flung chapel in Scotland; to an Alpine mountain pass; to the Vatican itself!

We had several false starts on the design (I wanted to overcomplicate it with multiple projectors at one point) and several false starts on where to put the thing (“Will it fit in the garage? Could we put it in a tent?”) We eventually decided to give up a major room in our chosen venue, because we lost one room and gained (potentially) a whole universe!

Avec Fromage et Jambon

It’s probably worth pointing out here that we’d already come to the conclusion that we wouldn’t be trying to be deeply immersive with much of the event – we would deliberately be making use of the players’ suspension of disbelief, their inventiveness, and their ability to not take things too seriously and to create play for others. The setting would be cheesy, with large slices of hamminess. That didn’t mean the roles wouldn’t be taken seriously – after all, in the 70s movies, everyone is taking their roles seriously. It just meant that we would emphasise the fun to be found in being deliberately collaborative with other players. This would be play to lift rather than play to win.

It’s About Time

With the High Road established as the place for Fighting Adventures (as we couldn’t really have fighting on the sound stage) and with the Sound Stage established as the place for Exotic Adventures (on sets we couldn’t build elsewhere), the shape of the event had evolved again.

We had lessons, and amongst them we had adventures; we also had, from the very beginning, a siege sequence, and a tavern brawl. Harry was most insistent on those. So how could we make it all fit together? It made very little sense that you could spend three days at a training school and in the middle of it pop off to Paris or the Vatican and come back an hour or so later.

We started to think about time.

In Dick Britton, we adopted a framework which we called Cinedrama. The conceit was that the whole event was actually a movie, which meant we could frame it like a movie and use movie concepts and ideas. We would call “Cut!” between scenes, as (for example) the players flew from Bavaria to the Arabian Desert, and “Action” when we’d walked them over to the desert set; we asked them to ignore the brown-coated stage-hands who were shifting scenery; we would get them to trace a dotted red line across a map while travelling; and everyone played everything through the lens of over-dramatic, hammed-up acting. Which fitted our cheese and ham approach perfectly.

And All for One was intentionally trying to recreate the feel of the 1970s musketeers movies. So – Cinedrama!

(You can learn a lot more about Cinedrama here.)

This meant that we could conceivably have cuts between scenes where large time spans took place. You wouldn’t join a musketeer academy on Friday and graduate on the following Sunday – surely it would take at least a year? And that journey to Paris would take a week, at least; not to mention the journey to far-flung Scotland!

We divided play into distinct acts. During an act, time would be linear. At the end of an act, we’d call “Cut”, and update people with how much time had passed and any major events they’d know about. Then we’d start play again, with a call of “Action!” Suddenly, months had passed.

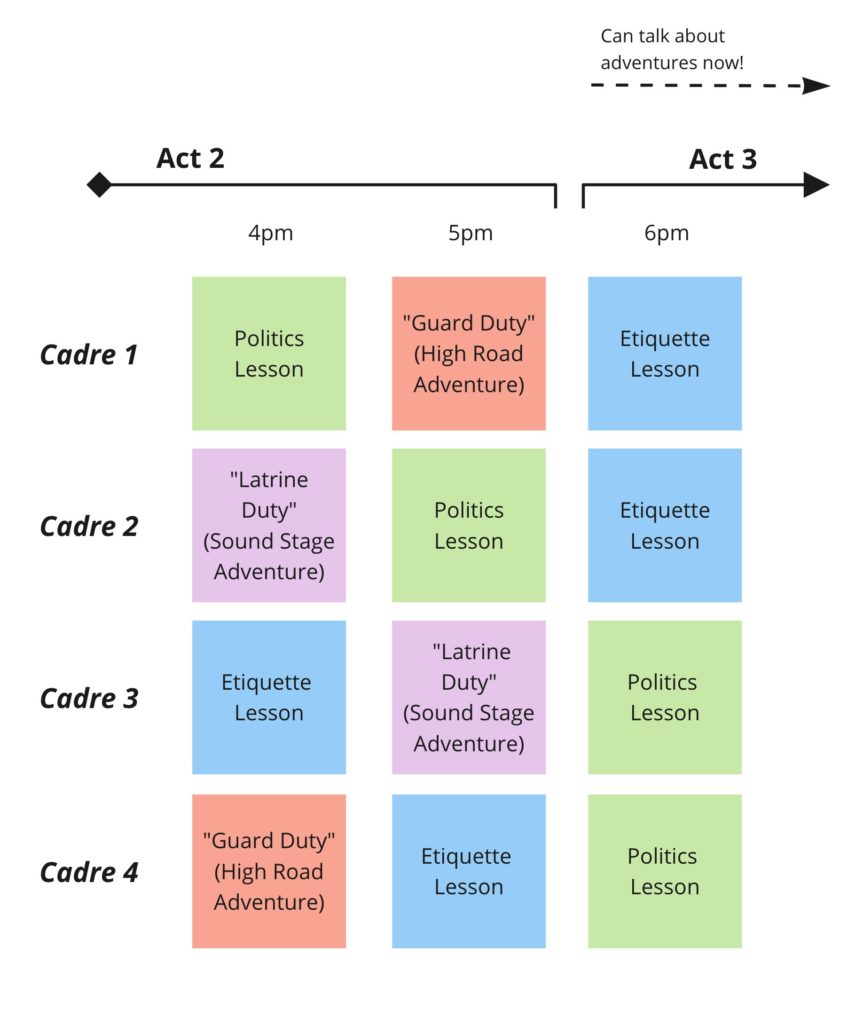

A small complication here is that we couldn’t have all the cadres having their adventures ‘between acts’ – it would have made sense from a game point of view, but logistically the scheduling for us was impossible.

But this is Cinedrama! Things don’t need to be filmed in order! Therefore, we fitted the ‘adventures’ into the normal academy timetable, disguising them as ‘Latrine Duty’ and ‘Guard Duty’. From the point of view of everyone in the academy, those cadres would be off on very unexciting duties for an hour. From the point of view of the cadres on the adventures, they’d be travelling hundreds of miles, perhaps over the course of several months. The gimmick was that, on returning to the academy, they couldn’t tell anyone else what had happened – because it hadn’t happened yet! After the next Act break, they’d be able to talk about it. Slightly convoluted, but worked surprisingly well in practice.

The Cinedrama framework was hugely helpful for both the High Road and Sound Stage as well. Being able to transport them huge distances or time spans with a simple ‘Cut’ meant the adventures became snappier, more focused, and more globe-trotting. For the sound stage in particular, we were even able to play with split-screen (simultaneous action happening on two separate bits of the stage), montages, and fast cuts back and forward between bits of action.

This cinematic conceit also meant we could put in music and sound effects and everybody would be happy to play along.

The Siege

Going back to our initial moments list, what about this siege? In the early parts of the design, we’d looked at transporting all the players off-site to an entirely separate venue where our stunt and props team had arranged a battle. In the end, we managed to fit it on to our existing site, with some clever work by the battle team, led by Kiera, Bill, and Chris.

Conceptually, the thing we wanted to nail for the siege design was for it to feel like a small group of musketeers – one cadre – was taking on hordes of enemies. But where would we get that horde of enemies? Well – how about the rest of the cadres?

So Cinedrama came to the rescue again. We would use the same piece of physical ground, but in the fiction of the game we were shooting five different parts of the siege scene from ‘different angles’. Between takes we would rearrange the battlefield. Each cadre would have their own take; their own mini-story and mission objective. And then, as they went on to the battlefield, they’d be faced by the players of the other cadres along with our supporting cast, all costumed up to be the enemy forces. Seven against fifty! After that attack was over, we’d call “Cut”, rearrange the field, and then it was time for the next cadre.

The siege became its own act within the overall story – taking back the Academy from Spanish forces!

Having a Ball

Another set-piece moment we had to have was a masked ball. Partly we wanted to watch our cadets navigate their way through a situation requiring etiquette and politics; partly we wanted to give them a chance to rub shoulders with all the major figures of the court; and partly we wanted to steal the humour and confusion from the scenes in Casanova and Shakespeare where there are multiple cases of mistaken identity. To do this we introduced a new cinematic rule. First we provided all the masks, making sure many were identical; then we introduced the rule that it was impossible for anyone to tell two people wearing the same mask apart, no matter how else they were dressed. We’ve all seen movies where the identity of the masked figure is utterly obvious, yet the rest of the cast just can’t seem to figure it out.

Faith in Cheeses

The set-piece moment that Harry had dreamed of was the tavern brawl. A scene in which each cadre would enter a tavern, have to fight with everybody inside, and during the confusion steal their dinner. We turned this over to our stunt and props team – they created foam chairs, tables, benches, and barrels for our cast to hit each other with. Their masterpiece was a foam chandelier that could be dropped on people’s heads. To all those, we added sugar-glass bottles and wine glasses, which could be smashed over combatants. Again, as with the siege, this scene would run five different times, once for each cadre; everyone having the opportunity to get stuck in! To minimise potential physical danger, we worked brawling into the lesson plan, so that by the time the cadets got to this scene they would already have had a chance to become familiar with a bit of stage fighting.

Building Story Threads

Having decided the shape of our game – the academy as a ‘hub’ with adventures taking place elsewhere; time broken down into acts; major set pieces such as the siege, the ball, the tavern, and the graduation ceremony, we now needed to look at how we would structure the story itself.

We had many, many different ideas for plots, inspired by the Musketeers movies and similar sources. We couldn’t run them all. But one single plot didn’t make much sense, as the cadres would effectively be sharing that plot between them and there wouldn’t be enough to do. It just didn’t fit our structure. But we had five cadres, so why not have five plots?

This was a fairly major turn in our design thinking. Instead of making one movie for a cast of thirty-five, we’d be making five movies, intertwined with each other, each for a cast of seven. This gave us a solid framework for how we’d try and make each cadre’s experience feel coherent and focused.

We decided to hang each story off a particular major figure from the movies. We’d already come to the conclusion that we’d set the story twenty years later, so that D’artagnan and his companions had moved on, giving the cadets a chance to be the new Musketeers. So we thought about what would have happened to the major characters in twenty years; where the interesting stories and conflicts might be. And we tried to mix things around, so that the Cardinal wasn’t necessarily the antagonist, and that the Queen wasn’t necessarily the damsel in distress.

As a result each cadre had a story focused around their interactions with one or two major supporting cast members, who represented a faction of the court; the Queen, the King, the Cardinal, the Captain of the Cardinal’s Guard, Lady De Winter and so on. While the stories did overlap, the main thrust and goal of each story was particular to a cadre. It also tied in ideas that the players had sent in about their particular cadre’s background and their individual character connections.

Juggling and Plate-Spinning

One of our hardest – and most-often revisited – tasks was to juggle the event timetable. We kept having discussions like: “Cadre Verte needs to be at the Soundstage at 2pm, but they can’t go to Paris at that point, because they have to learn about the current political climate during their 3pm lesson with Aramis! And we need Aramis on the High Road earlier in the day, so he can’t tell them then.” It was mind-numbing, and kept changing and changing again. We had the whole event timetabled before we realised that having horses and black powder weapons together at the same time would not be a good idea and had to change it. Again! Before the event Rachel painstakingly extracted all the information into sorted spreadsheets and printed them out. We never thought it’d survive contact with the event itself. And were astounded when almost everything ran exactly to schedule.

Character Generation

To create the characters – and to see what stories our players might be interested in us writing – we used our Tag System, which I’ve written about over here. Rather than submitting full characters, players submit a set of tags describing their character, which the writers then work from.

The Rules

We created a bespoke rules system based on moments from our moments list – to help us provoke the scenes we wanted to happen between the players. You can find the rules here.

For example, we wanted the cadre to have a motto, so that they would clash blades and shout their equivalent of ‘All for One!’. We worked that in as a healing mechanic – if your cadets and servants were all wounded and tired, they could clash swords, shout their motto, and be healed.

We introduced and systemised the idea of ‘Heroic Moments’ so that each player could have a moment in the limelight where they had the advantage over the opposition.

We turned the servants into the ‘healing batteries’ of the cadre, so that the cadre were utterly dependent on their servants (and would protect them). When a cadet was injured, the servant could pour them a tankard of wine and give them a good talking to, and they’d soon be on their feet again.

We added back in our language rules from Dick Britton, so that people could have the opportunity for a moment where everyone knew perfectly well what was said, but their characters didn’t.

We introduced duelling rules, so that people who were not great at sword fighting in reality could still feel like a true musketeer and win duels. And we made fighting very, very simple.

In general we tried to get the rules as out of the way as possible, with very little to remember; tried to make them so that there was plenty of room for individual improvisation; and above all tried to make them create opportunities to have those moments from our list.

Into The Pot

Into all this, we also threw:

- Messengers turning up on horseback. Real horses in a larp game was something we’d wanted to do for years. Happily, Rachel is a vet, and trained to run a riding stable.

- Real black-powder firing muskets, so players could actually be musketeers! Tim and Jon, who provided the muskets, also fired cannon for us across the battlefield.

- Pyrotechnics, including hand grenades and a bomb to breach a wall, by David.

- A superb supporting cast, some of whom taught lessons on politics, herbalism, brawling, swordplay, and dancing, and some of whom switched characters twenty times in the course of an hour.

- A catering team, cooking banquets and buffets for all and sundry, and for one evening an improvised seven-course gourmet dinner for a small number of cast and players.

- Background music for the high road and the sound stage, and music for the grand ball, provided (and in some cases created) by Panda, our dance instructor.

- A working alchemical experiment to prove that one key plot item was real, and another faked.

- Opening titles with a text-crawl, and closing titles listing the cast and crew.

- An Iron Mask; a Holy Relic; the Stone of Scone (and the fake Stone of Scone); a Templar altar; a gravestone with a coffin buried beneath it, complete with a nun’s corpse; the Fallen Madonna avec Les Grands Melons by Van Clomp (and a forgery of same); a mortar you could hammer a spike into; a flat-pack boat; six nun’s outfits; a set of false moustaches… and all manner of other props and effects and costumes and ridiculousness.

And Finally

Like all our productions, everything here was tailored as much as possible to help us deliver those moments from our initial list. Either actual set pieces, or situations or rules which would give the players the opportunity to create or experience one of those moments. We wanted to make them feel like they were part of a Three Musketeers movie. That’s really our philosophy for all this sort of design: start with what you want the players to feel, and work back from that.

Photos courtesy of Tom Garnett.

Over here, you can find Harry talking about the bits he was happiest with, including some scenes I’d forgotten about.

We couldn’t have done this without the help of a huge number of skilled and creative individuals. I’ve named some. You can find the other names in the end credits:

If you’re interested in more of this sort of thing, here’s a complete contrast — my write-up of some of the design aspects of Wing and a Prayer, a larp/simulation of the duties of the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force during World War 2. Or there’s an entire website over here about our 1950s ghost story, God Rest Ye Merry.